Azurite Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

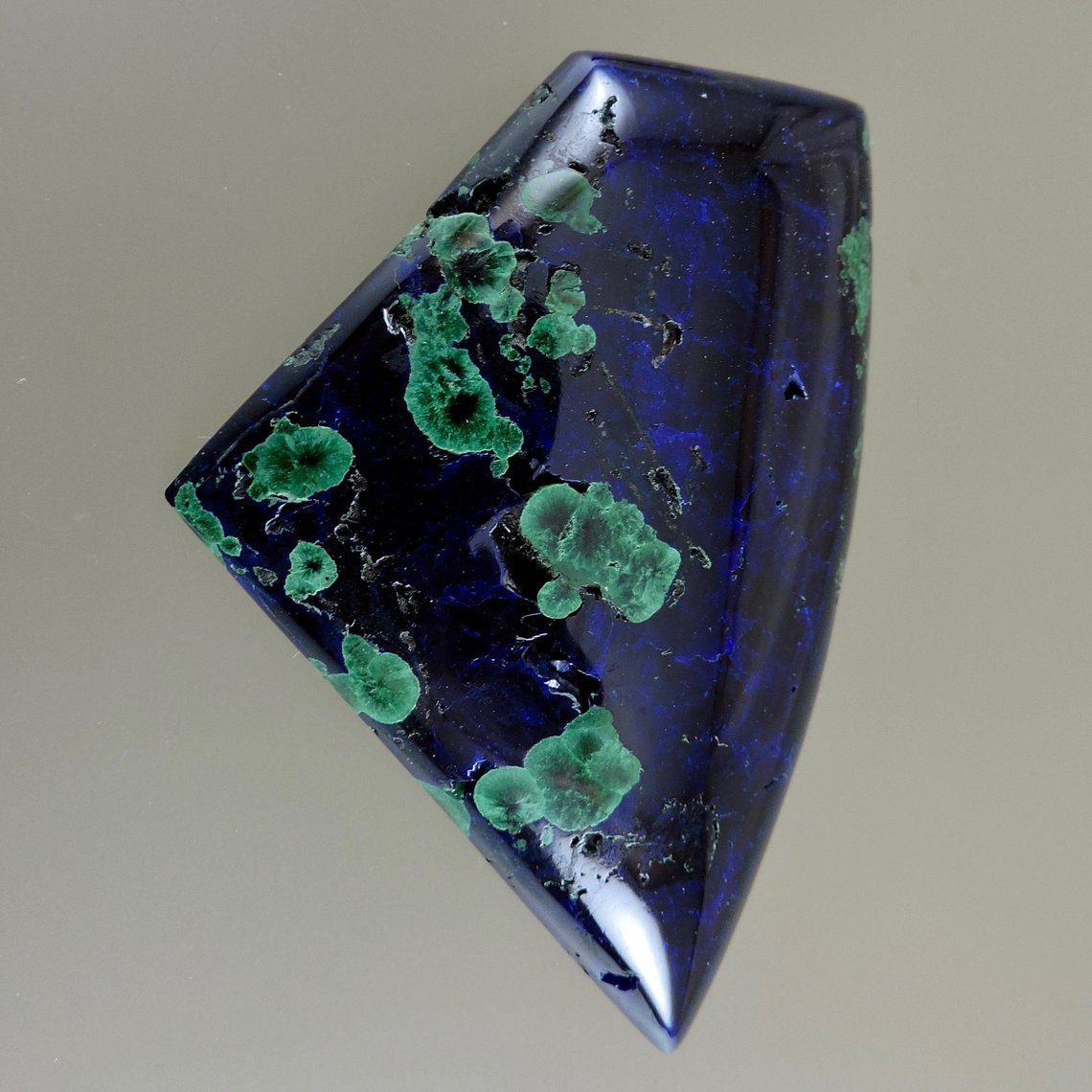

Collectors prize deep blue azurite crystals, but faceted gems are extremely rare. However, azurite frequently occurs mixed with green malachite, and this material is commonly used for cabochons and decorative objects.

4 Minute Read

Collectors prize deep blue azurite crystals, but faceted gems are extremely rare. However, azurite frequently occurs mixed with green malachite, and this material is commonly used for cabochons and decorative objects.

Start an IGS Membership today

for full access to our price guide (updated monthly).Azurite Value

What is Azurite?

Azurite occurs in fine crystals in many localities. When it occurs in massive form, the material is almost always mixed with malachite, another copper carbonate mineral. Lapidaries cut this mixture, called azurite-malachite or azurmalachite, into very attractive cabochons and large decorative items, such as boxes.

Burnite is a mixture of azurite and cuprite (copper oxide).

Since azurite is more unstable than malachite, it often pseudomorphs into malachite. This means its chemistry changes to malachite while retaining azurite's external crystal form.

How Does Azurite Get Its Color?

Azurites, malachites, and cuprites are all idiochromatic; they receive their color from copper. However, copper creates different colors in these different species. Azurites are always blue, malachites are always green, and cuprites are always red. When they occur mixed, these minerals appear as bands and/or "eyes" of their distinctive colors.

Does Azurite Make a Good Jewelry Stone?

Azurite's distinctive, intense blue color makes it a popular collector's stone. However, even small azurites are extremely dark, virtually black. Since azurites have such low hardness (3.5-4) as well as perfect cleavage, brittle tenacity, and great sensitivity to heat, faceting them proves very challenging. This combination of factors makes faceted azurites very rare.

Azurites will also gradually lose their blue color when exposed to air, heat, and light. Thus, reserve these gems for occasional jewelry use with protective settings.

Azurites make less than ideal jewelry stones. Cut gems may appeal more to collectors of unusual stones or aficionados of gem cutting skill.

Are Azurites Toxic?

Although the normal wearing or handling finished azurites should pose no health hazards, gem cutters should take precautions when working with these gems. Azurite's copper content makes its dust toxic. Accidental ingestion could lead to acute distress, like vomiting, and chronic exposure could lead to liver and kidney damage. Faceters should wear protective masks and, ideally, use a glovebox to prevent inhaling or ingesting azurite particles during cutting and polishing.

How Can You Distinguish Azurites from Lapis and Other Blue Stones?

Artists have used blue pigments made from azurite since ancient times. Perhaps not surprisingly, people have confused this stone with lapis lazuli, another well-known historic source of blue pigments. Sodalite, another gem material commonly cabbed and carved, is sometimes confused with azurite as well.

Although these materials may show similar colors, azurites have a higher refractive index (RI) and specific gravity (SG) as well as a lower hardness. Azurites are also birefringent, while lapis and sodalite are not.

Are There Synthetic Azurites?

Scientists have synthesized azurites for geological research as well as research into pigments. Crystals have also been created in labs. However, due to azurite's physical limitations, any such lab-created material would make an unlikely option for jewelry use.

Reconstituted Azurmalachite

Nevertheless, you can easily find "synthetic azurites" for sale online, especially in jewelry. Be aware that "reconstructed" azurmalachite — a compressed and stabilized, plastic-impregnated form of azurite and malachite — can be cabbed and has good color and toughness. This material has been available since 1989 at the latest, and by 1992, imitations of azurmalachite in jewelry were popular (if not always convincing). More recently, such materials have been found to contain artificial veins of copper.

It's possible vendors are selling this "reconstructed" material or other simulants as "synthetic." In such cases, "synthetic" means imitation or "fake" in the popular sense. These stones aren't identical optically and physically to the natural, mined material. Buyer beware.

"Copper Lapis" and "Arctic Opal"

Although natural azurite is a coveted collector's stone, it's still not very well-known to consumers. Thus, some vendors may misrepresent azurites as "copper lapis" or "Arctic opal," perhaps to garner more sales interest by associating them with more popular gems. Of course, azurites aren't lapis or opals but a distinct gem species.

See our article on false or misleading gemstone names for more examples of misrepresented gems.

Azurite Enhancements

Azurites generally receive no treatments or enhancements. ("Reconstructed" azurmalachite may receive pore-filling stabilization treatments similar to turquoise).

Where are Azurites Found?

Notable gem-quality localities include the following:

- United States: Morenci and Bisbee, Arizona: banded and massive material, also crystals; Kelly, New Mexico (also other localities in that state).

- Chessy, France: the type locality, material sometimes called chessylite, fine crystals in large groups.

- Eclipse Mine, Muldiva-Chillagoe area, Queensland, Australia: gemmy crystals up to about 9 grams.

- Tsumeb, Namibia: fine, tabular crystals, some facetable in small bits.

- Zacatecas, Mexico: fine but small crystals.

- China; Democratic Republic of Congo; Greece; Italy; Laos; Morocco; Pakistan; Peru; Russia.

Stone Sizes

Facetable crystals are always tiny, and cut gems rarely weigh more than a carat. Larger stones would most likely be so dark as to be opaque. Gem cutters sometimes take dark blue crystalline material and create cabochons up to several inches across.

How to Care for Azurites

Clean these gems only with water, mild detergent, and a soft brush. Avoid any cleaner that contains acids. Store them separately from harder jewelry stones, in darkness, and sealed to reduce contact with air.

Consult our gemstone jewelry cleaning guide for more care recommendations.

Joel E. Arem, Ph.D., FGA

Dr. Joel E. Arem has more than 60 years of experience in the world of gems and minerals. After obtaining his Ph.D. in Mineralogy from Harvard University, he has published numerous books that are still among the most widely used references and guidebooks on crystals, gems and minerals in the world.

Co-founder and President of numerous organizations, Dr. Arem has enjoyed a lifelong career in mineralogy and gemology. He has been a Smithsonian scientist and Curator, a consultant to many well-known companies and institutions, and a prolific author and speaker. Although his main activities have been as a gem cutter and dealer, his focus has always been education. joelarem.com

International Gem Society

Related Articles

Black Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Chameleon Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Gray Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Green Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Latest Articles

Quartz Toxicity: Understanding the Risks for Jewelers and Wearers

Synthetic Amethyst: What is it and How is it Made?

Hambergite Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Pearl Simulants: How to Spot Faux Pearls

Never Stop Learning

When you join the IGS community, you get trusted diamond & gemstone information when you need it.

Get Gemology Insights

Get started with the International Gem Society’s free guide to gemstone identification. Join our weekly newsletter & get a free copy of the Gem ID Checklist!