Smithsonite Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Smithsonite occurs across the globe, but facetable crystals are extremely rare. These gems can show a wide range range of rich colors but are too soft for most jewelry use. However, high dispersion makes properly faceted smithsonites truly magnificent collector’s pieces.

3 Minute Read

Smithsonite occurs across the globe, but facetable crystals are extremely rare. These gems can show a wide range range of rich colors but are too soft for most jewelry use. However, high dispersion makes properly faceted smithsonites truly magnificent collector’s pieces.

Start an IGS Membership today

for full access to our price guide (updated monthly).Smithsonite Value

What is Smithsonite?

Smithsonite belongs to the calcite mineral group. It also forms a series as the zinc-dominant (Zn) end member with iron-dominant (Fe) siderite.

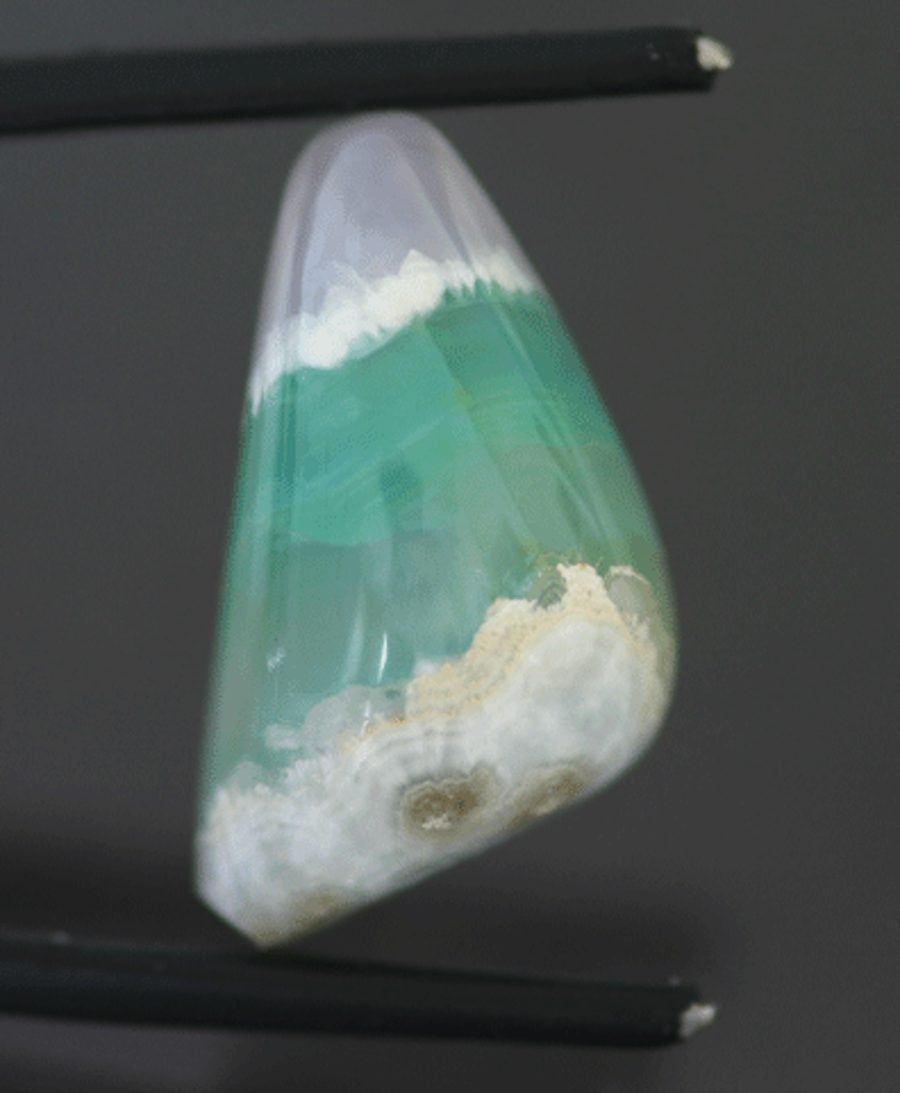

For many years, collectors have prized blue-green smithsonites from New Mexico and yellowish stones from Tsumeb, Namibia. However, varieties in many stunning colors exist, including deep yellows, apple greens, pinks, and purples.

Some references may cite traces of cadmium as the cause of yellow, cobalt as the cause of pink, and copper as the cause of green and blue in smithsonites. However, research on the causes of color in this gemstone continues. For example, some pink specimens identified as "cobaltian smithsonites" proved to have no cobalt under further examination.

Does Smithsonite Make a Good Jewelry Stone?

Regardless of the causes, the colors of faceted smithsonites benefit greatly from this gem's considerable dispersion or "fire." Unfortunately, relatively low hardness and perfect cleavage leave these gems vulnerable to damage from everyday wear as jewelry stones. Reserve these gems for occasional wear or pieces with protective settings. For instance, pendants and earrings would make excellent jewelry choices.

However, smithsonite's cleavage can also make it a difficult material to cut. Thus, few faceted stones are available for jewelry. You're more likely to find smithsonites in a mineral collection than a jewelry collection.

Identifying Characteristics

Smithsonite effervesces in warm acids. Please keep in mind that acid testing is a destructive test. It can endanger both the gem and the tester. Never conduct this test on a finished gem. Use this procedure on rough as a last resort for gem identification only.

Birefringence

Faceted smithsonites may show a doubling of back facets when viewed through the table due to high birefringence. However, such stones must have considerably greater transparency than typical.

Cabbed smithsonites will show a "birefringence blink" when examined through a refractometer.

Luminescence

Under shortwave ultraviolet light:

- Medium whitish blue (Japan)

- Blue-white (Spain)

- Rose red (England)

- Brown (Georgia, Sardinia)

Under longwave ultraviolet light:

- Greenish yellow (Spain)

- Lavender (California)

Are There Synthetic Smithsonites?

Geologists have synthesized smithsonite (a zinc ore) for research purposes.

Evidently, "synthetic smithsonite" does occasionally appear in jewelry. However, an online search for such pieces doesn't clarify whether this material is actually lab-created or just a simulant or "imitation." These may be instances of the term "synthetic" used in the more popular sense of just simply "not real."

Smithsonites are somewhat porous. Thus, some pieces may receive oil treatments to enhance their luster or surface coatings to prevent discoloration.

Where is Smithsonite Found?

The Kelly Mine in Socorro County, New Mexico, USA produces celebrated blue and blue-green material of fine color in massive crusts.

Most facetable material comes from African sources. Tsumeb, Namibia produces yellowish, pinkish, and green facetable crystals. Broken Hill, Zambia also yields transparent crystals to 1 cm.

Mexico produces material with much variation in color, including bi-colors, as well as pink and bluish crusts. The pink material from Mexico is especially lovely.

Laurium, Greece yields fine blue and green crystals.

The Masua and Monteponi mines in Sardinia, Italy once produced translucent, deep yellow, banded material. However, these mines are now closed.

Other notable sources include the following locations:

- United States: Marion County, Arkansas (yellow, banded crusts); California; Colorado; Georgia; Montana; Utah.

- Algeria; Australia (yellow material); Austria; Belgium; China; France; Germany; Japan; Spain; Tunisia; United Kingdom.

Stone Sizes

Lapidaries can cut beautiful cabochons up to many inches from massive material from New Mexico, Sardinia, and other localities. Crusts in some localities are several inches thick. Facetable crystals are rare, and stones over 10 carats could be considered exceptional.

- Private Collection: 45.1 (dark yellow, emerald-cut. Tsumeb, Namibia).

How to Care for Smithsonites

Store smithsonites separately from other harder, more common jewelry stones.

Since smithsonites are somewhat porous, don't wear them while applying perfumes or other sprays. Avoid wearing them directly against your skin. Clean these gems only with a soft brush, mild detergent, and warm water, but don't soak them. See our jewelry cleaning guide for more recommendations.

Joel E. Arem, Ph.D., FGA

Dr. Joel E. Arem has more than 60 years of experience in the world of gems and minerals. After obtaining his Ph.D. in Mineralogy from Harvard University, he has published numerous books that are still among the most widely used references and guidebooks on crystals, gems and minerals in the world.

Co-founder and President of numerous organizations, Dr. Arem has enjoyed a lifelong career in mineralogy and gemology. He has been a Smithsonian scientist and Curator, a consultant to many well-known companies and institutions, and a prolific author and speaker. Although his main activities have been as a gem cutter and dealer, his focus has always been education. joelarem.com

International Gem Society

Related Articles

Faceting Tips for Exotic Gemstones

Black Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Chameleon Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Gray Diamond Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Latest Articles

Amethyst Sources Around the World: The Geological Story Behind These Purple Gemstones

Brazilianite Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

Ruby-Glass Composites vs Leaded Glass Clarity Enhancements

Morganite Buying Guide

Never Stop Learning

When you join the IGS community, you get trusted diamond & gemstone information when you need it.

Get Gemology Insights

Get started with the International Gem Society’s free guide to gemstone identification. Join our weekly newsletter & get a free copy of the Gem ID Checklist!